Sara Bédard-Goulet and Bruno Goosse

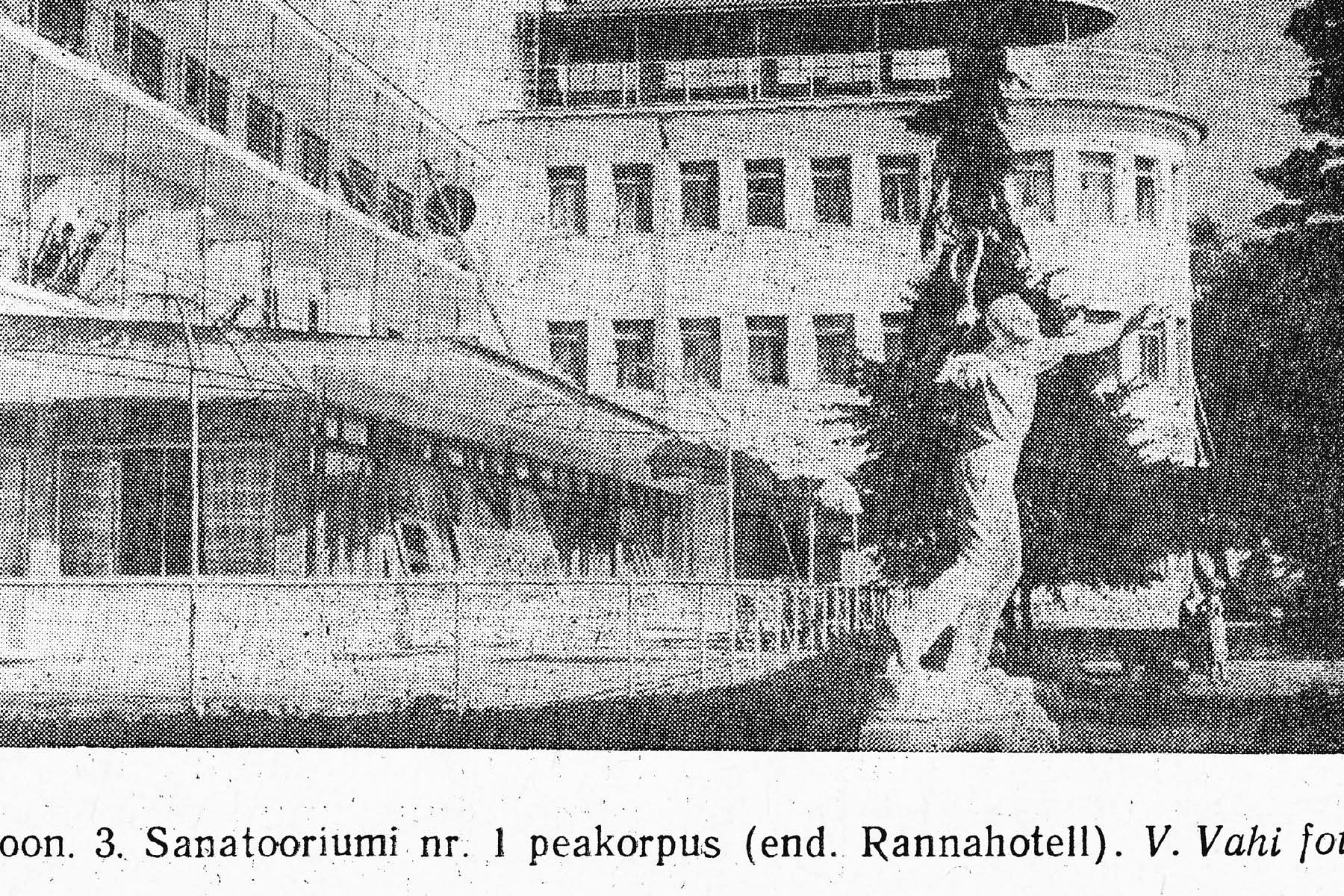

Sanatorium Atmosphere is the title of an artistic research presented as an exhibition in Tartu (Estonia) and in Vilnius (Lithuania) in the autumn 2020 and 2021.

These exhibitions were part of a larger research-creation project, called Response Events, which focused on how experiencing cultural and artistic representations can sometimes lead to life-changing events for readers or spectators.

Sara initiated this project at the University of Tartu in cooperation with Aix-Marseille University and Côte d’Azur University (France). The project led to the organization of a conference, a doctoral workshop, three exhibitions in Tartu, one in Vilnius, and to the publication of several articles as well as one special issue of the Interdisciplinary Literature Studies journal.

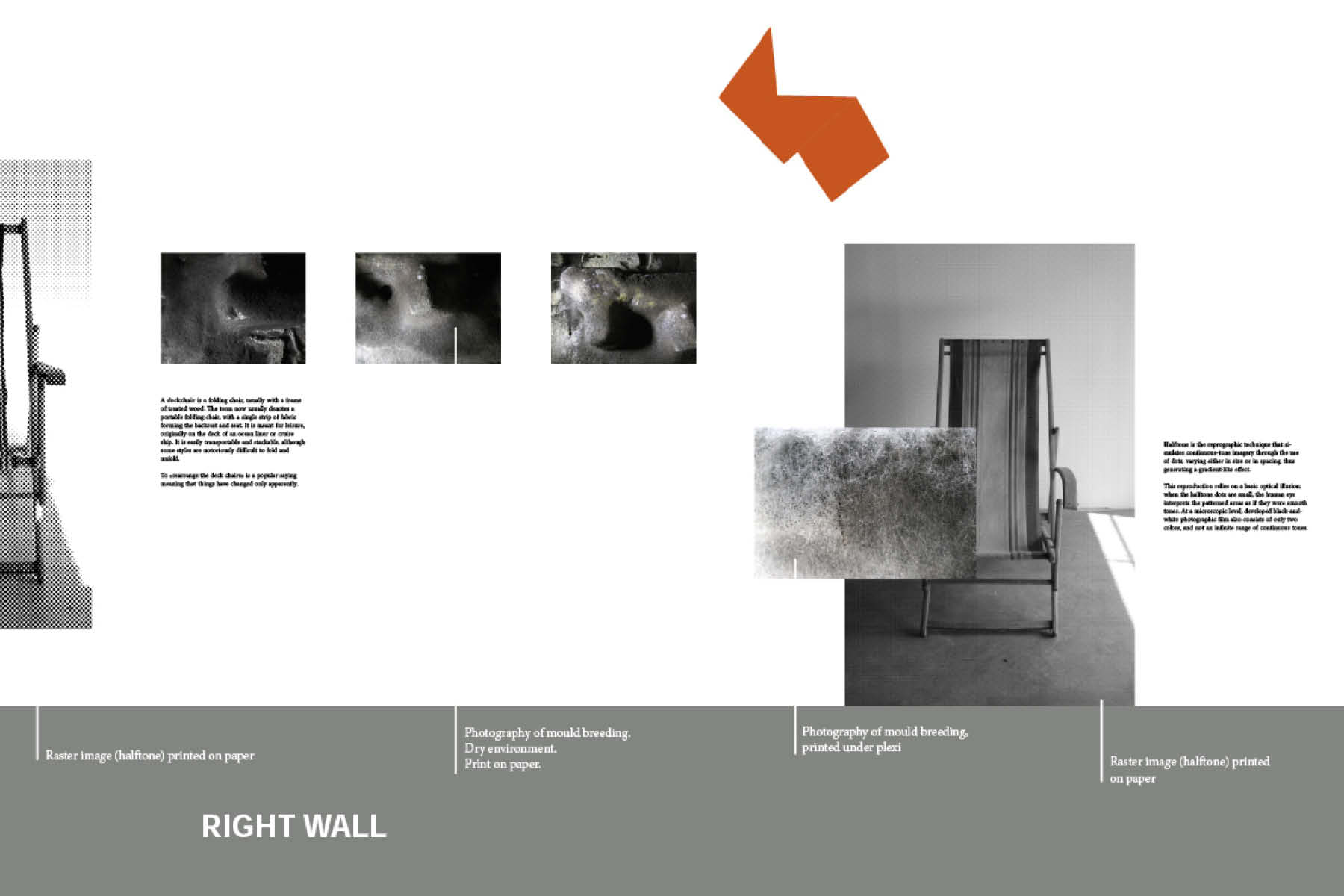

Sanatorium Atmosphere was first presented as a solo show at Kogo gallery and then in a group show at Titanikas gallery of Vilnius Academy of Arts.

When I invited Bruno to join the Response Events project, he was working on the creation of sanatoriums as a response to a public health problem. We had the yet still confused impression that the sanatorium could be an event and that it had to do with reception.

When we learned that the word “sanatorium” did not carry the same meaning in Eastern Europe then in Belgium and France, we thought that it was a topic to be developed in the Baltic context. This difference of meaning augured a difference of reception. Incidentally, the pandemic invited itself in the work without being called. It was difficult to avoid it as the world still composes with the pandemic’s rhythm.

It is clear that the situation created by Covid-19 is not only a health problem (that concerns health specialists) but also a political one. The authorities’ role in managing the health crisis is a commonplace, to a point that we judge the governments’ politics based on what we consider a properly handled health crisis.

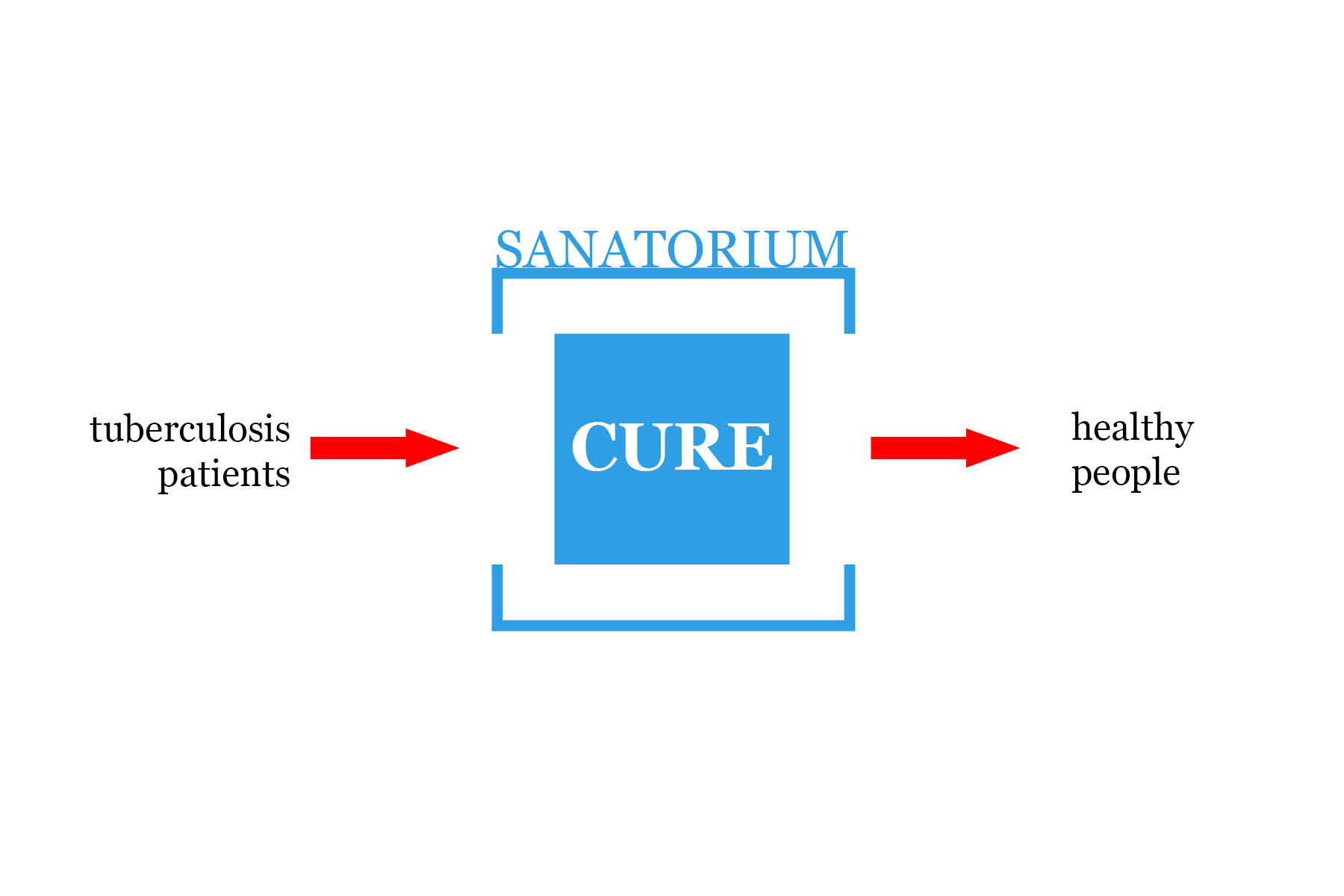

Yet, this connection between politics and health is not self-evident. The creation of public sanatoriums as a means to fight tuberculosis exemplifies the political role regarding health (perhaps not everywhere but definitely in France, in Belgium, etc.).

Tuberculosis is a very old disease. It is believed that it has always accompanied humans. But pathological descriptions were only unified in the 19th century and identified to TB, that is when it became a true epidemic and a political problem.

Tuberculosis became a political problem at the end of the 19th century because it mainly affected young men and women fit to work. The industrial revolution brought new life conditions for those who became workers: poorly fed and lodged, exhausted by never-ending work days, living in close proximity in unseen before human density.

These life conditions favored the spread of tuberculosis. It devasted the workers. By attacking the working force necessary to run industries, the epidemic was attacking the countries’ economy and becoming a political problem. The states had to find a solution.

From a scientific perspective, at the end of the 19th century, Koch has identified the responsible bacteria, the tubercle bacillus. This bacillus is extremely resistant. There was no way to destroy it then but it was known to be sensitive to sunlight exposure.

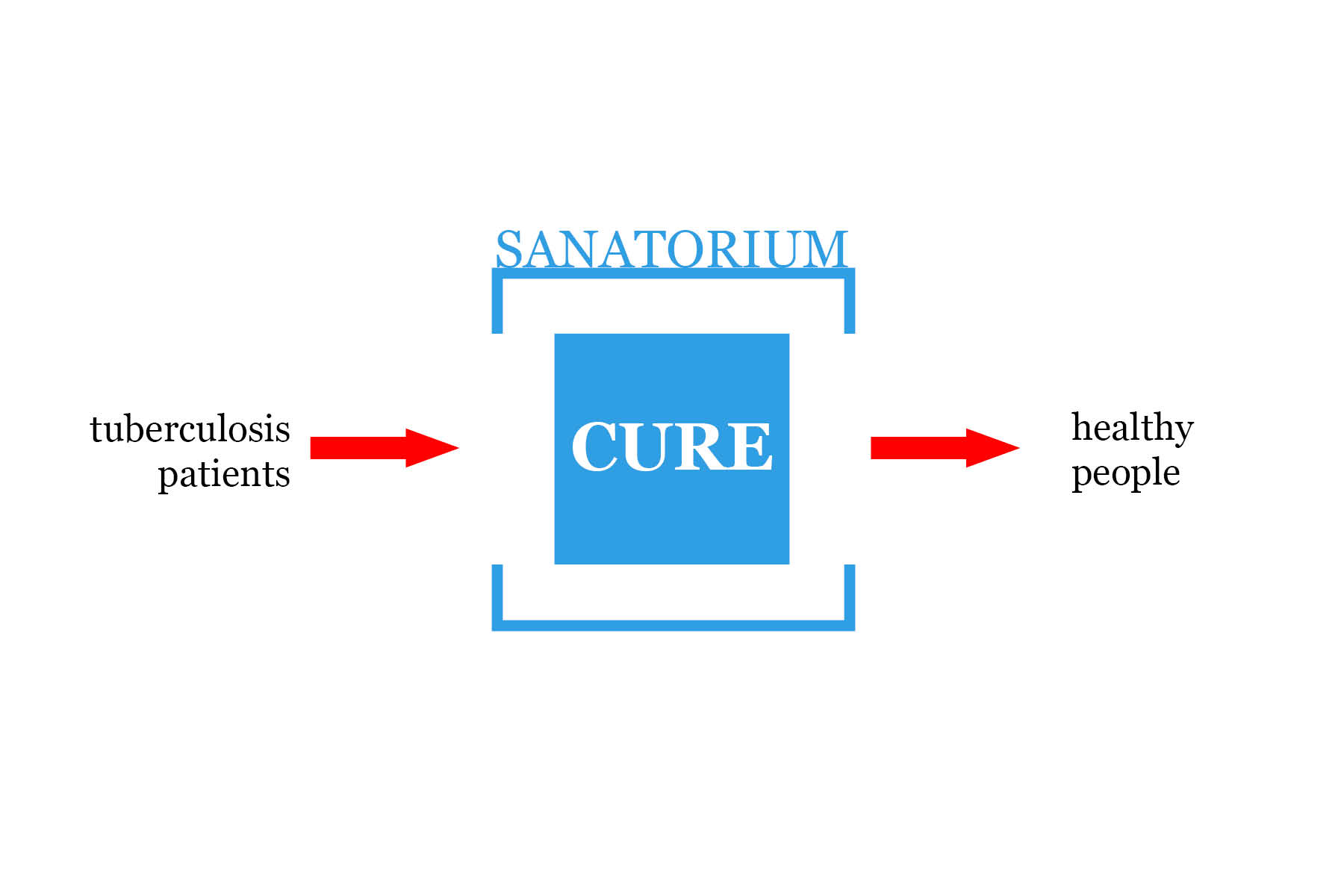

It was also known that the disease was contagious. The treatment offered to the diseased was a cure of air, sun, rest and abundant food. This cure was relatively effective for lightly ill patients.

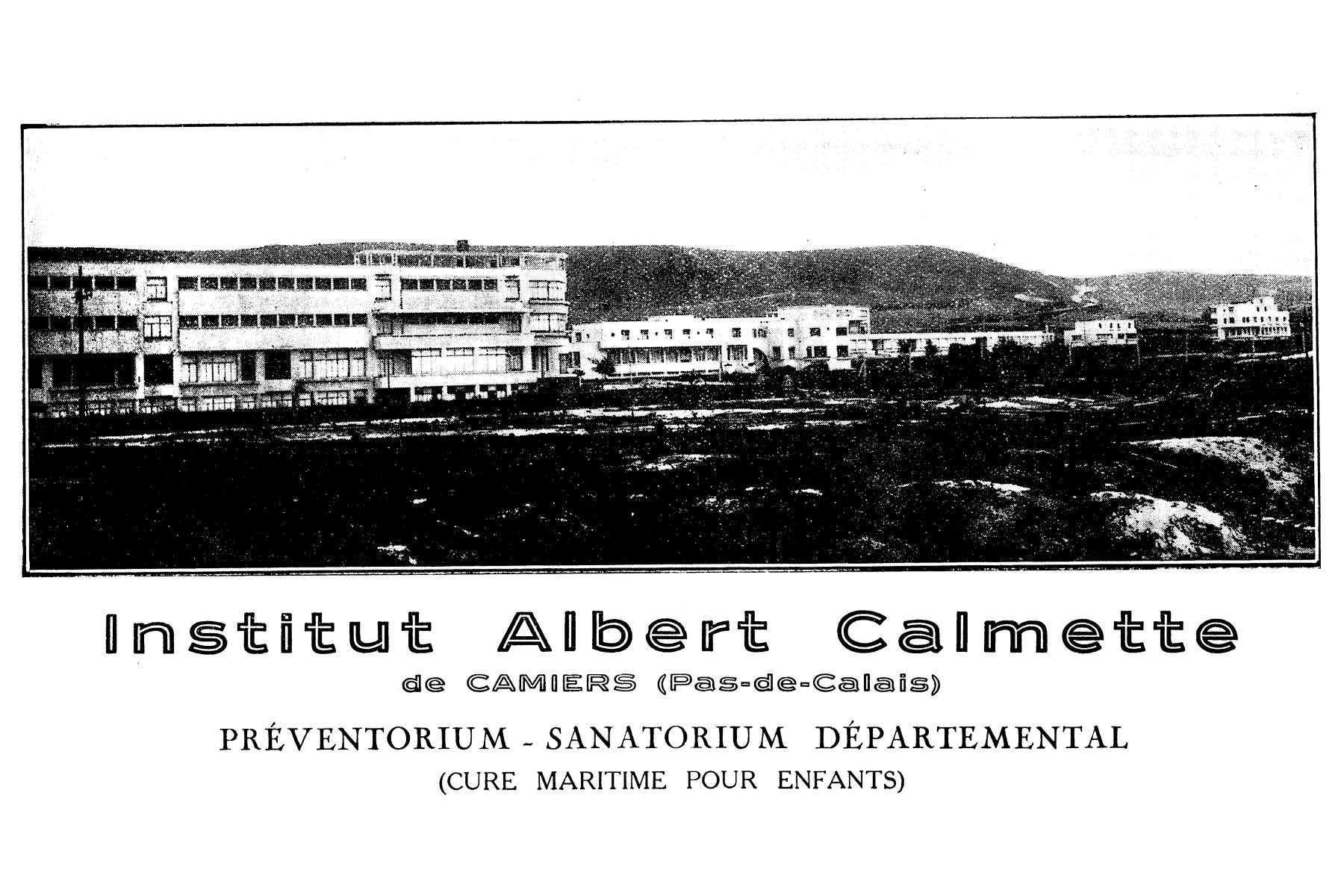

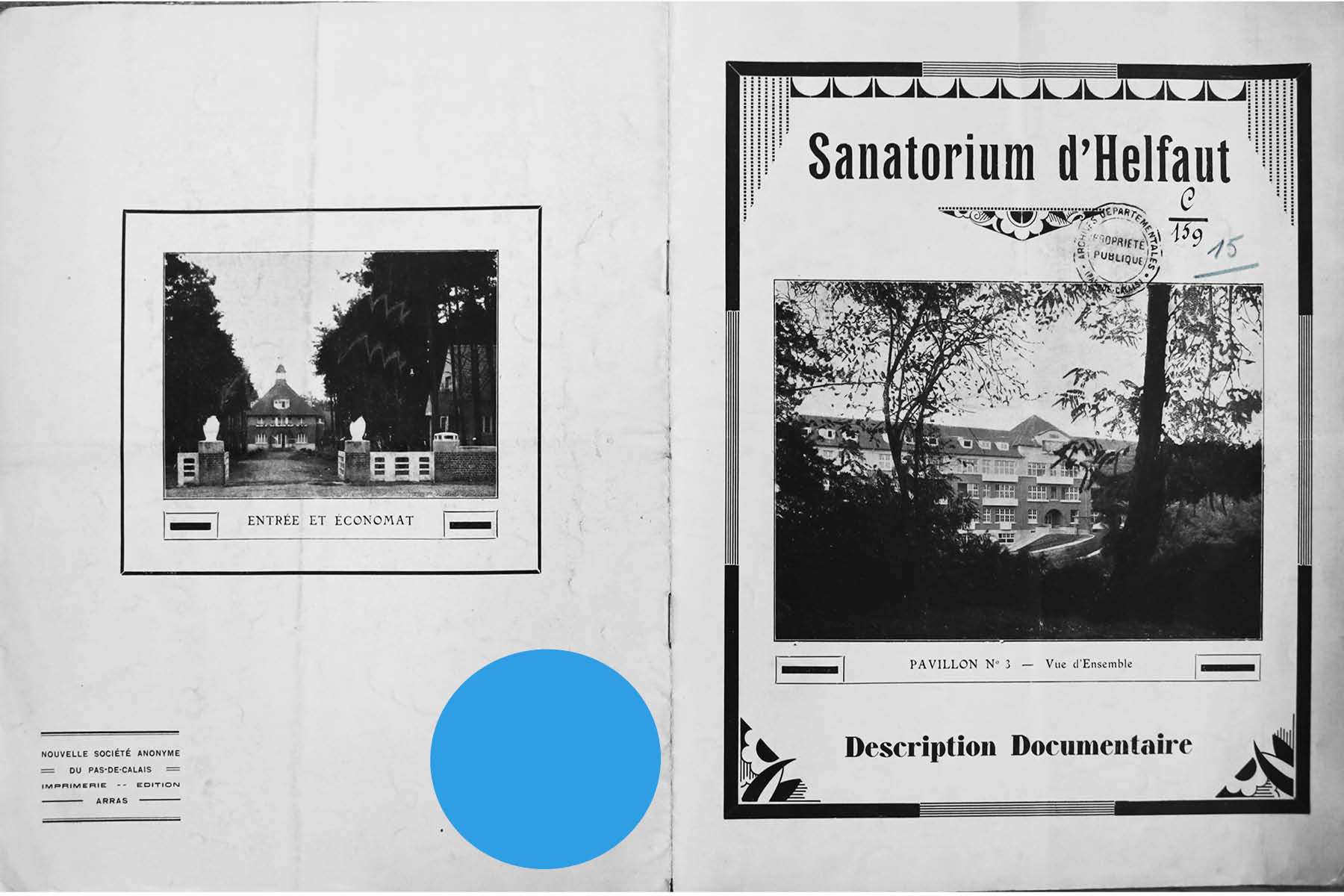

In 1854, Hermann Brehmer, a German natural scientist cured from TB after a stay in the Himalayas, designs a building adapted to this cure in Görbersdorf (now Sokołowsko [Sokowofsko] in Poland). He dedicated himself to medicine and published about his achievement. The sanatorium was born: a building designed to have an effect to its occupants’ health.

In France, between 1900 and 1950, 250 public sanatoriums were built.

From a Western-centric point of view, the sanatorium is a place meant to isolate the sick and cure them in a way that was generally agreed upon at the end of the 19th century: with air, sun, rest and abundant food.

With the creation of sanatoriums, medical science raised as a power organizing the patients’ ways of life. (What some people have discovered during the lockdowns resulting from Covid and against which they spoke out, claiming their right of freedom.)

In France and in Belgium, during the interwar period, each sanatorium was governed by regulations that stemmed from a legislative apparatus, which set a strict schedule and a list of authorized or forbidden actions and behaviors.

Art 48 – The users are required to follow the establishment’s schedule exactly. No modification can be made, even about details, without the authorization of the Doctor-Director. The rising, the meals, the cures and the extinction of the lights are announced to the user by an appropriate signal; they must comply to it as soon as the signal is heard.

This control applied in the name of the medical knowledge does not only concern the patients’ body. It intends to apply to her/his mind too.

Art 46 – The patients come to the sanatorium to learn how to take care of themselves and to take a complete physical and moral rest for a determined period of time, subordinating everything to the needs of the cure. When the doctors consider that the conditions allow it, the patient will be trained, if necessary in a gradual and methodical way, to resume work and to return to active life.

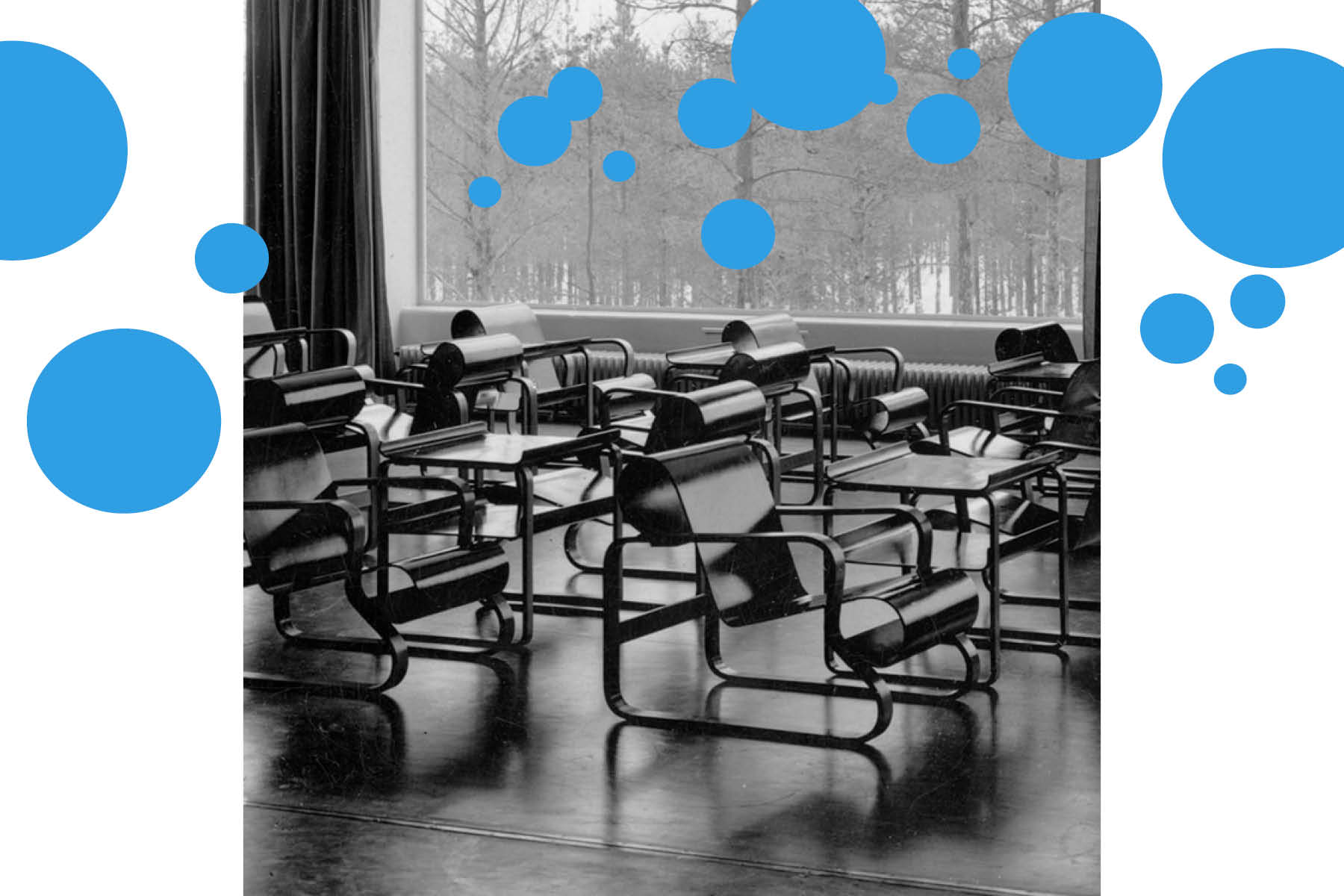

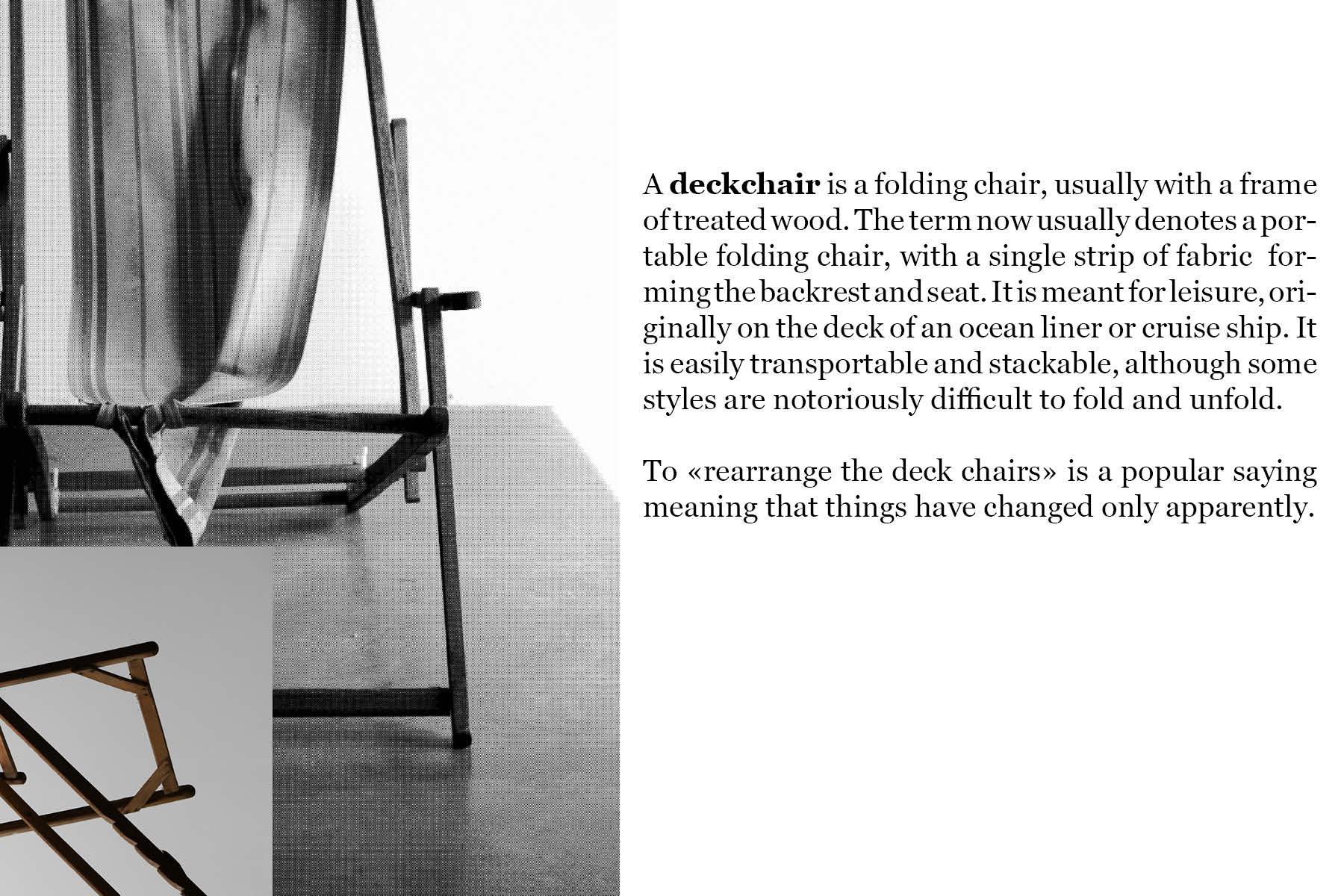

The day was marked by rest periods called rest cures (of about 3 times 2 hours), during which the patients had to mandatorily lie on deckchairs, sometimes in silence.

The patients must be constantly stretched out on their respective recliners. Singing, shouting, and loud laughter, which disturb the general rest, are forbidden; even conversations must be very moderate, as talking causes coughing. During the after-dinner and evening treatments, silence is required. Patients must not change places without permission. Deck chairs must not be dragged, moved or knocked over and must only be used for the rest cure.

It is about “Subjecting everything to the cure’s necessity.” Which does not seem far from what we have been into until recently. The treatment’s necessity has dictated and will no doubt dictate again our ways of living.

Patients must thus conform to strict rules that correspond to a scientific-medical normalisation of ways of living and to behave according to the disease. The fact that there is only one way to behave means that each body, including our own body, is identical to other bodies since it reacts the same way as them.

It is a kind of disembodiment. The patient separates themselves from their own bodies as the locus of sensations, both perceived and perceiving, felt and feeling. In the sanatorium, the patient’s body is observed, examined, objectified by the other, the doctor, by their devices of measurement and later of vision through the bodies. The thermometer tells the patient that they have fever, the X rays tells that they have a spot on a lung.

Because the disease cannot be perceived.

“Painless, inconsistent disease, clean disease, without smell, without ‘it’; it had no other marks than its time, interminable” “one was sick or cured, abstractly, by a pure decree of the doctor” […] “Isolation is its only palpable manifestation” wrote Roland Barthes, who stayed, as a teenager, in a sanatorium: the disease seems absent, invisible, because “we do not suffer”.

Roland Barthes par Roland Barthes, Seuil, Paris, 1975, p. 39.

The ill body is seemingly absent, it is perceived by the doctor only; the body feeling that it is not perceived. In the sanatoriums, the care of the patient’s body and spirit by medical knowledge is total.

Contrary to what happened with Covid-19, the sanatorium only isolates and confines the sick. Whereas lockdowns or quarantines concern the healthy as much as the sick.

However, if the distinction between sick and healthy is reassuring, it is not so easily established. We can wonder whether it is always possible to establish. Let me read a few lines from Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain (1924), in which Hans Castorp visits his cousin Joachim in Davos’ sanatorium. There he meets Doctor Krokovski for the first time:

– You are welcome, mister Castrop! I hope that you will quickly get used to this place and that you will find yourself at ease among us. Are you coming here as a patient, if I may ask? […]

He answered by talking about his three weeks, referred to his exam and added that, thank God, he was completely healthy.

– Really? asked Doctor Krokovski, moving his head forward obliquely, as if to mock, and his smile accentuated. In this case, you are a phenomenon worthy of being studied! Because I have never met an absolutely healthy man

And when the meeting ends, he concludes:

Well, sleep well, mister Castorp, in the full conscience of your perfect health. Sleep well, and good bye!

It is obvious that the whole book will constantly play on this knowledge’s fragility: to be or not to be healthy. Hans Castorp will finally stay seven years in the sanatorium instead of the three weeks initially planned. Yet, he did not suffer from tuberculosis.

If, like Thomas Mann suggests, the distinction between the sick and the healthy is not as easy to establish as we can think, then the sanatorial device, based on separation, is shaken.

Separation of the sick and the healthy, separation of the healthy ways of living and the pathogenic ones, separation of the healthy and hard-working places to live, separation of the medical body from the sick body, of the feeling body from the felt body, etc.

Moreover, in the public sanatoriums intended for the working classes, in order to convince the patient to leave their family for a very long treatment (or rather, the spouse to let his or her husband or wife leave for one, two, or several years), the separation of men and women was also a constant preoccupation, as if to double the previous separations, to the point that, in France, from 1920 onwards, a sanatorium was either destined exclusively for men, or exclusively for women, with particular rules for children.

From a societal perspective, the invention of sanatoriums was a means of preserving the social body by isolating the contagious sick from the healthy.

Most often built at a distance from urban areas, they had vast walking areas to avoid any outings. But this logic of isolation only makes sense if the distinction between the sick and the healthy can be established.

For many, tuberculosis is the archetypal disease of time: chronic, recurrent, progressive. But what happens when the disease of time meets the classification of space? The formal classification twists, categories run rampant, seeking a way of expressing the elusive flow of time. The gap between systems of knowledge and situated experience introduces the idea of texture. The look and feel of being in a place and using a genre of representation highlights the body’s presence in space and time, in an atmosphere. (Geoffrey C. Bowker & Susan Leigh Star. 2016. Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. Cambridge: MIT Press.)

Today, a number of these distinctive logics constituting our social scaffolding are discussed, criticized or even refuted, in favor of fluid, mobile distinctions, variable according to contexts, inducing rather logics of progression, of slipping from one state to another: one thinks of gender issues, of psychic disorders, of certain chronic illnesses, of work and distance work, etc.

It is a question of identifying the moments when what seems to us discontinuous, seen from another angle, shows a logic of continuity. And it seems to us particularly interesting to note, when reading Thomas Mann, that the sanatorium was already crossed by this tension, likely because it was a place where the body was central.

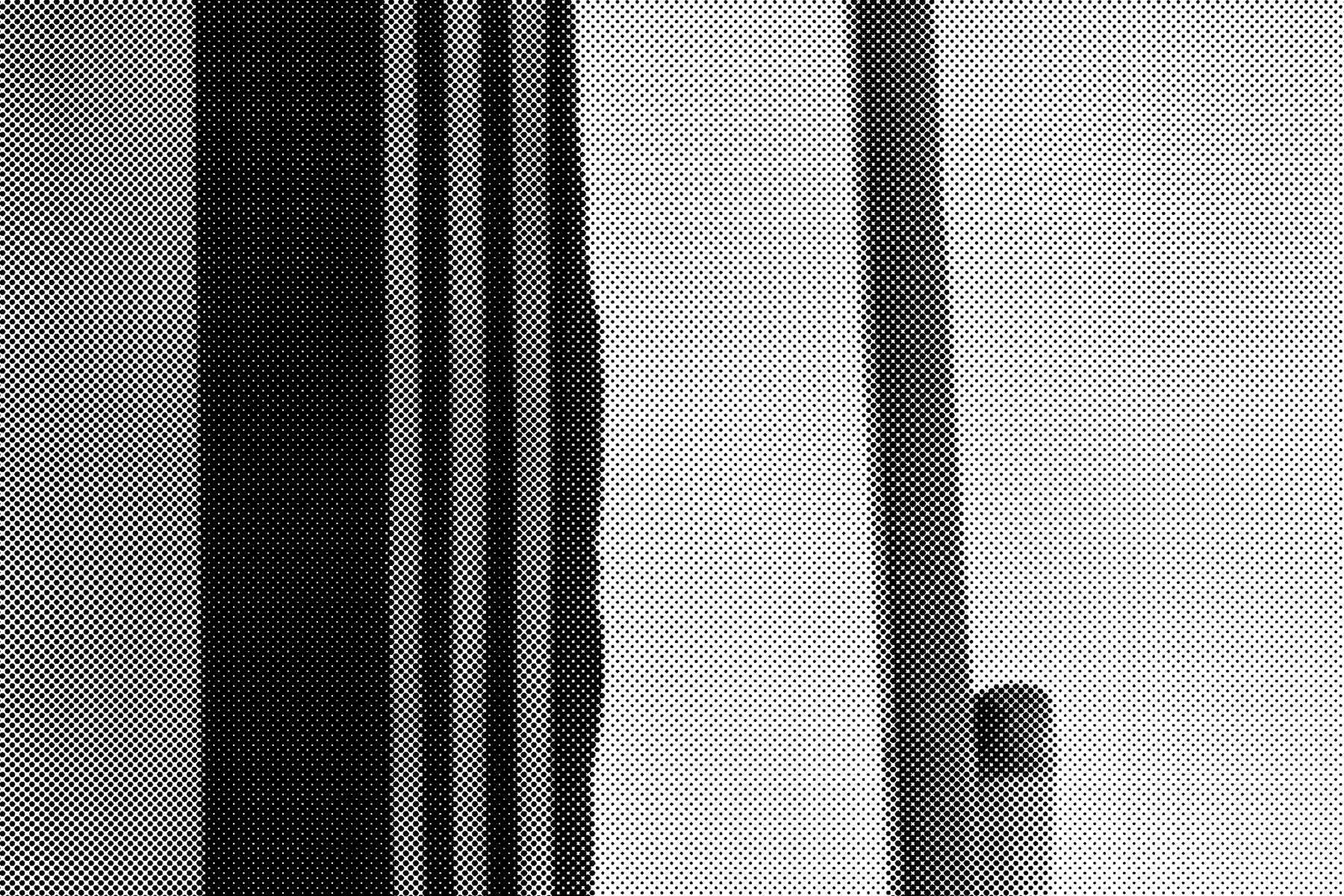

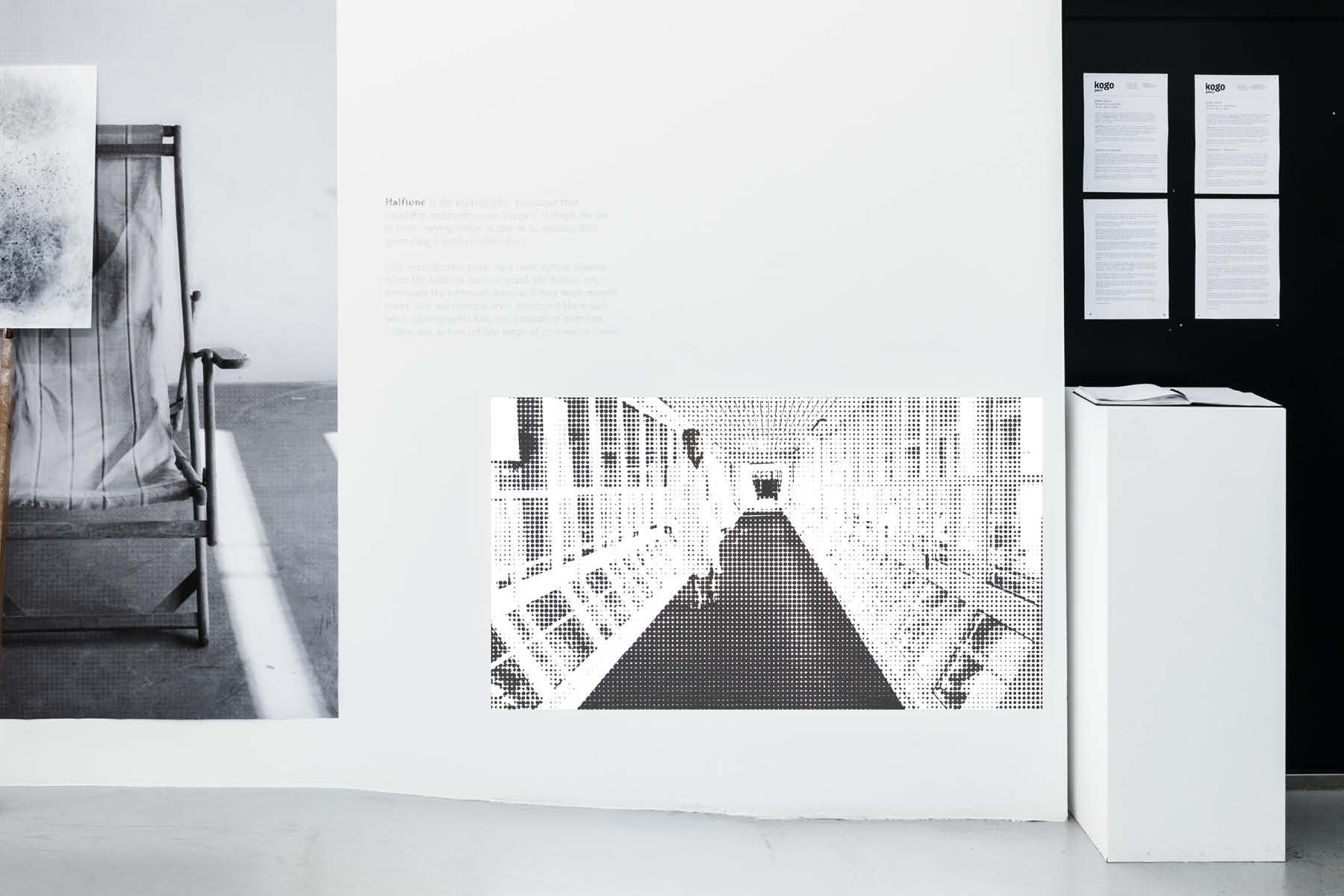

This question of transition from the continuous to the discontinuous is also an artistic question, even a technical one. Take the halftone, for example: this technique which transforms an image containing values of gray, gradations, continuities in a number of dots of different sizes, in order to be printed on rotary presses. What is interesting is that for printing, we transform the continuous into discontinuous but the eye, at a certain distance, recreates the continuous. Thus, continuous and discontinuous are well put in tension as long as one does not play only on the illusion

And it is perhaps no coincidence that the distinction between healthy and unhealthy wavers in the sanatorium itself. For the sanatorium is a paradoxical architecture. On the one hand it isolates. On the other, it connects. The rules try to repeat the game of separations to the point of nausea, while the architecture tries to put in relation.

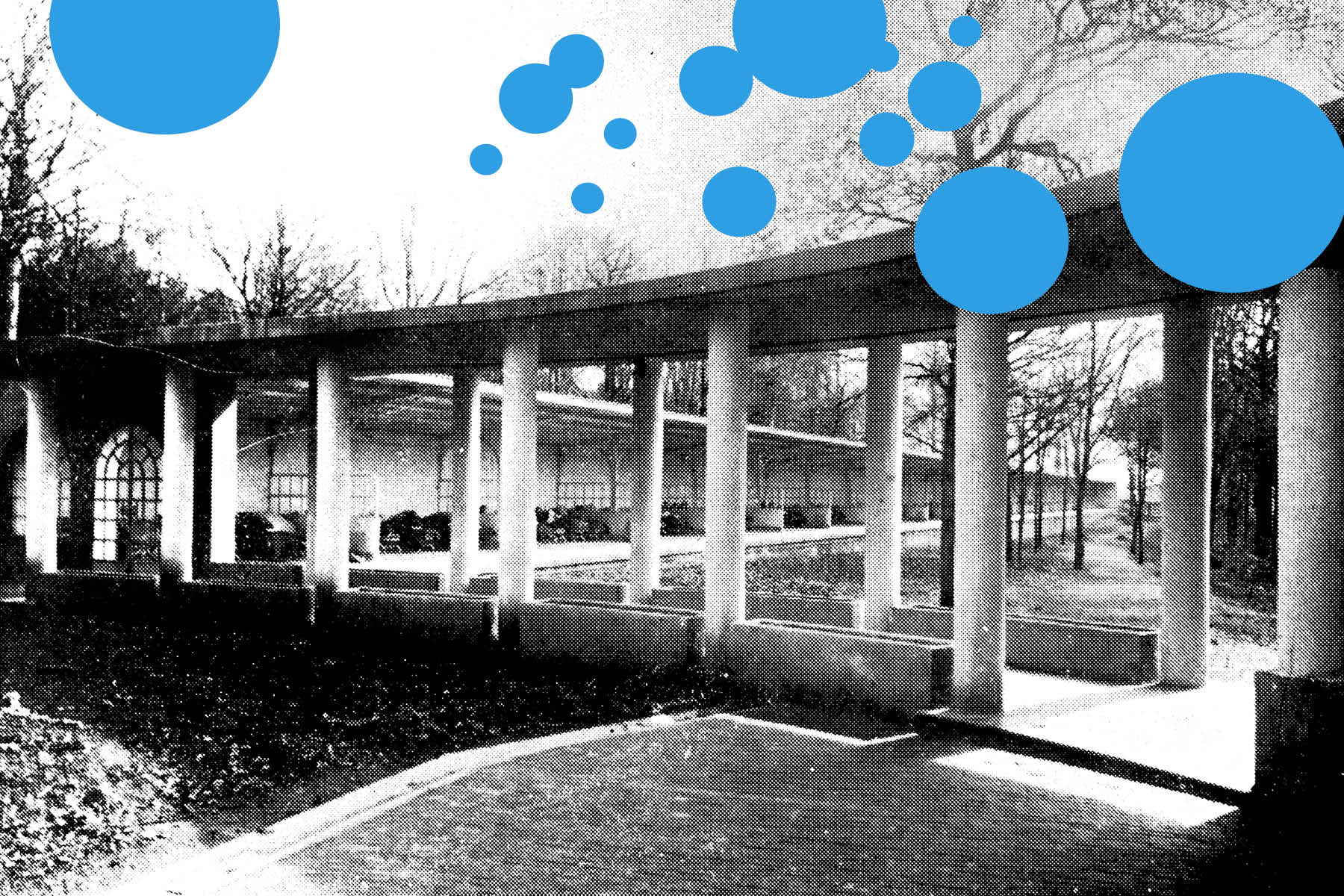

We can say that the sanatorium is a paradoxical architecture. Its main architectural characteristic is the presence of constructive elements that allow for air cure.

Art 5. Every sanatorium must have treatment galleries adjoining the rooms or galleries next to the rooms, where each patient must be able to rest in the open air, in bed or in a deck chair.

Décret n°48-806 du 24 mai 1948 relatif à la création, l’aménagement, le fonctionnement et la surveillance des aériums. Conditions d’installation et de fonctionnement des sanatoriums pour tuberculeux pulmonaire, Journal officiel de la République française, 26 mai 1948.

Yet, Vitruvius has rather accustomed us to identify the first human shelters as the first architectural gestures. The purpose of architecture is therefore protection. By building a shelter, men and women protect themselves from their environment, considered as hostile. The sanatorium, whose primary purpose is not to isolate from the outside world but rather to promote exchanges between the inhabitants and their environment, undermines this model.

Seen from this angle, we can speak of paradoxical architecture, or architectural exchanger. It is, in any case, a particular way of articulating separation, isolation and connection, exchange and this is what the exhibition Sanatorial Atmosphere proposed.

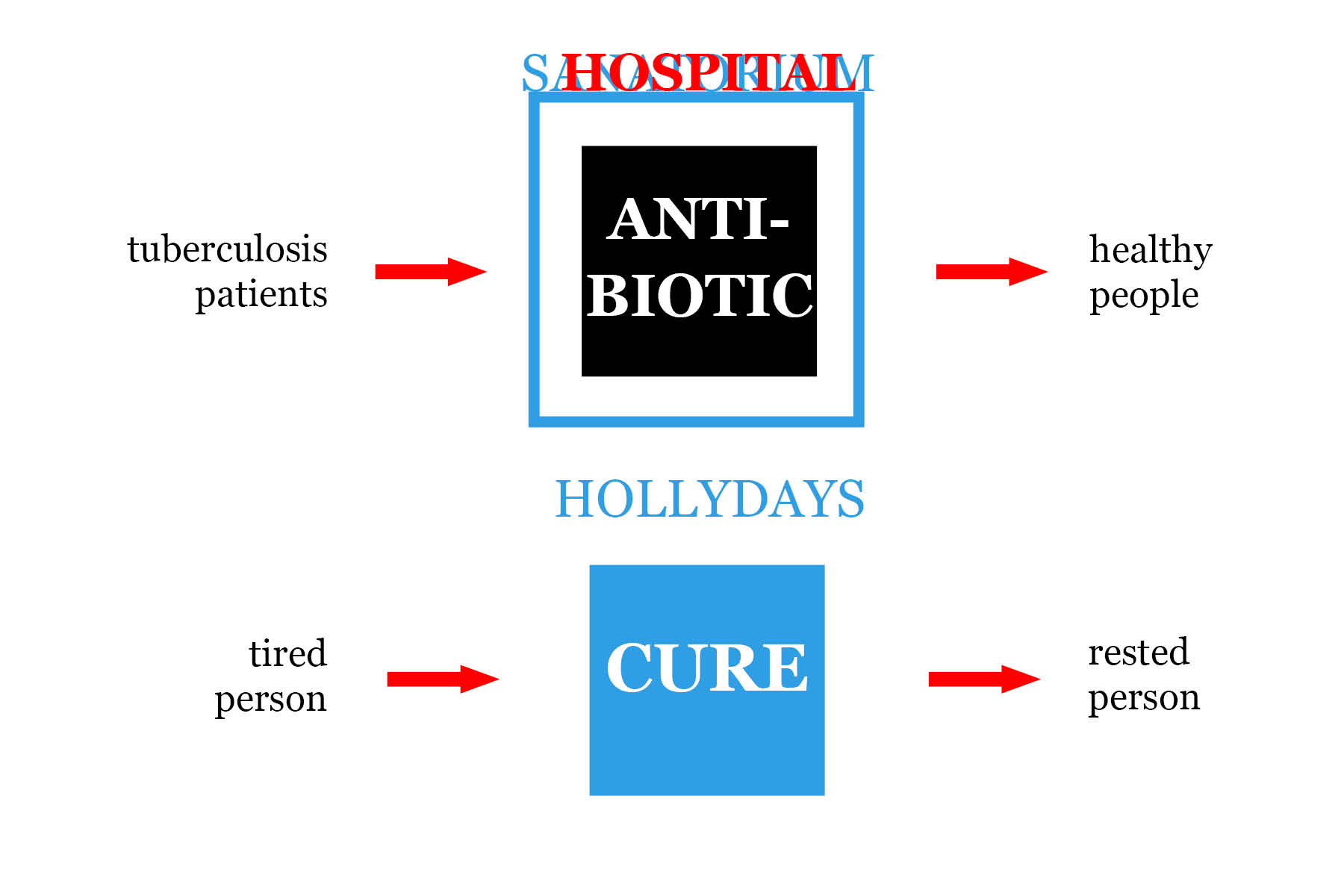

Western sanatoriums all referred to the idea of illness and death. But at the same time, curiously, the method recommended can make one think of what the mass tourism which develops after the second war will promote: rest, sunbathing, eating and drinking well, and fresh air…

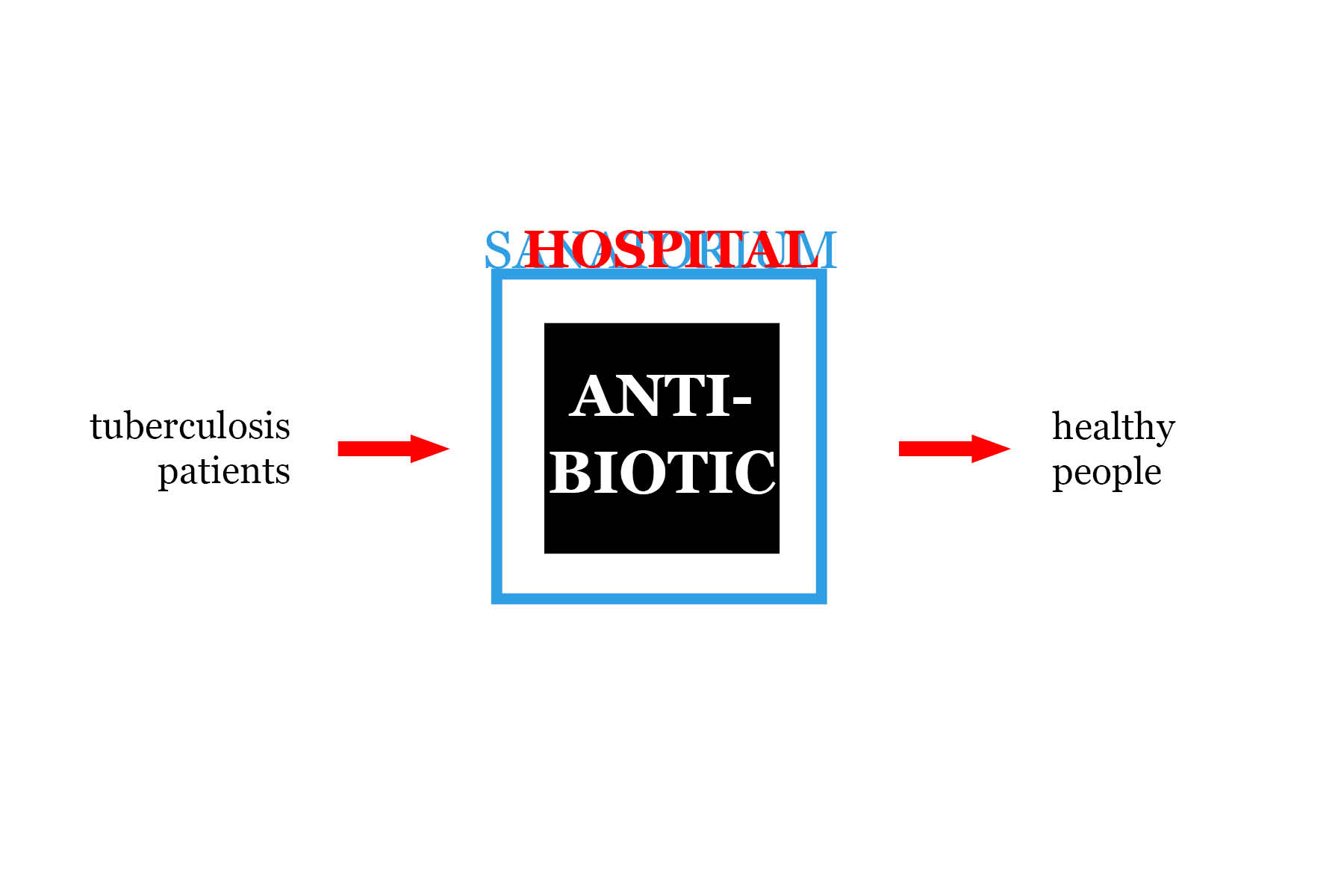

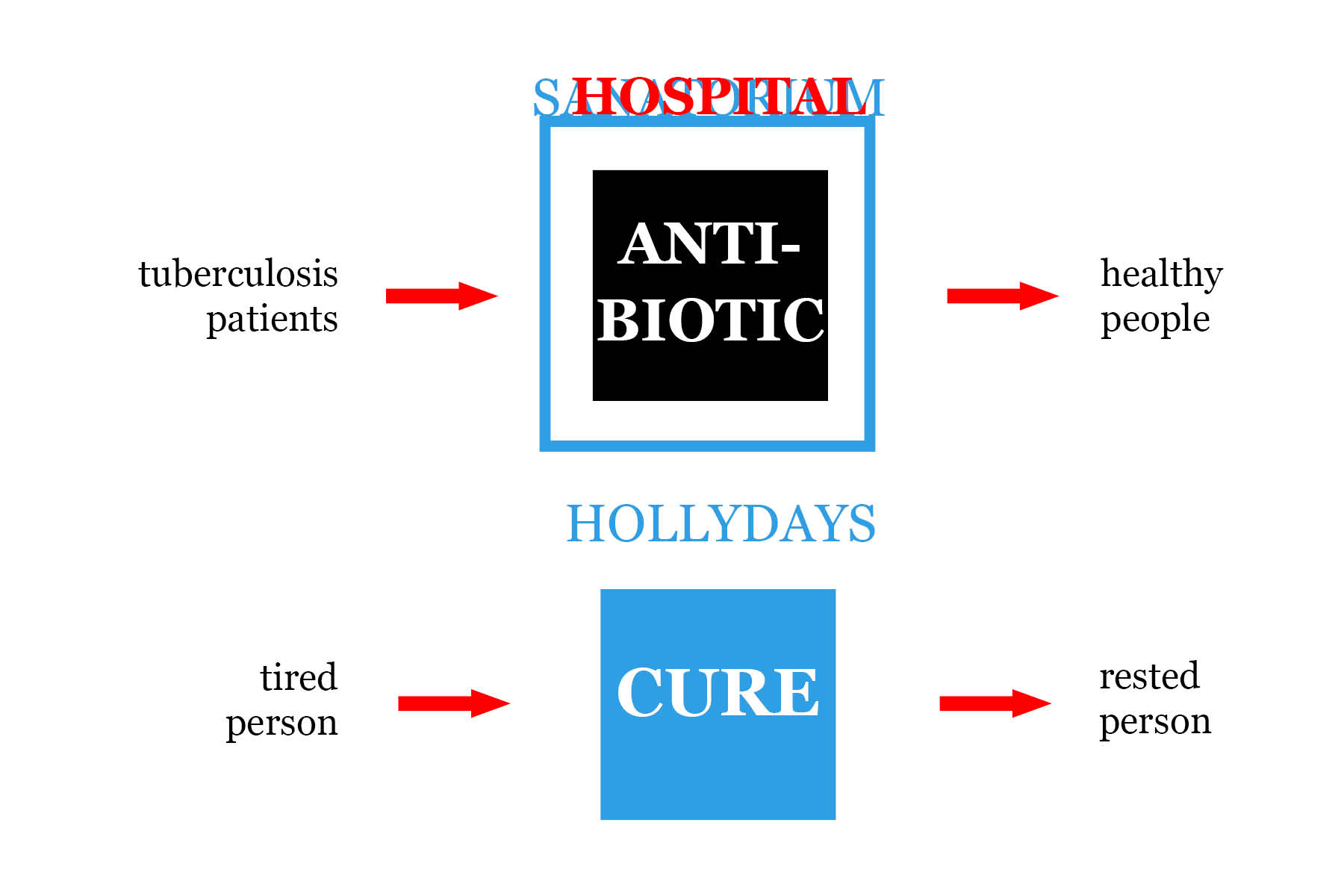

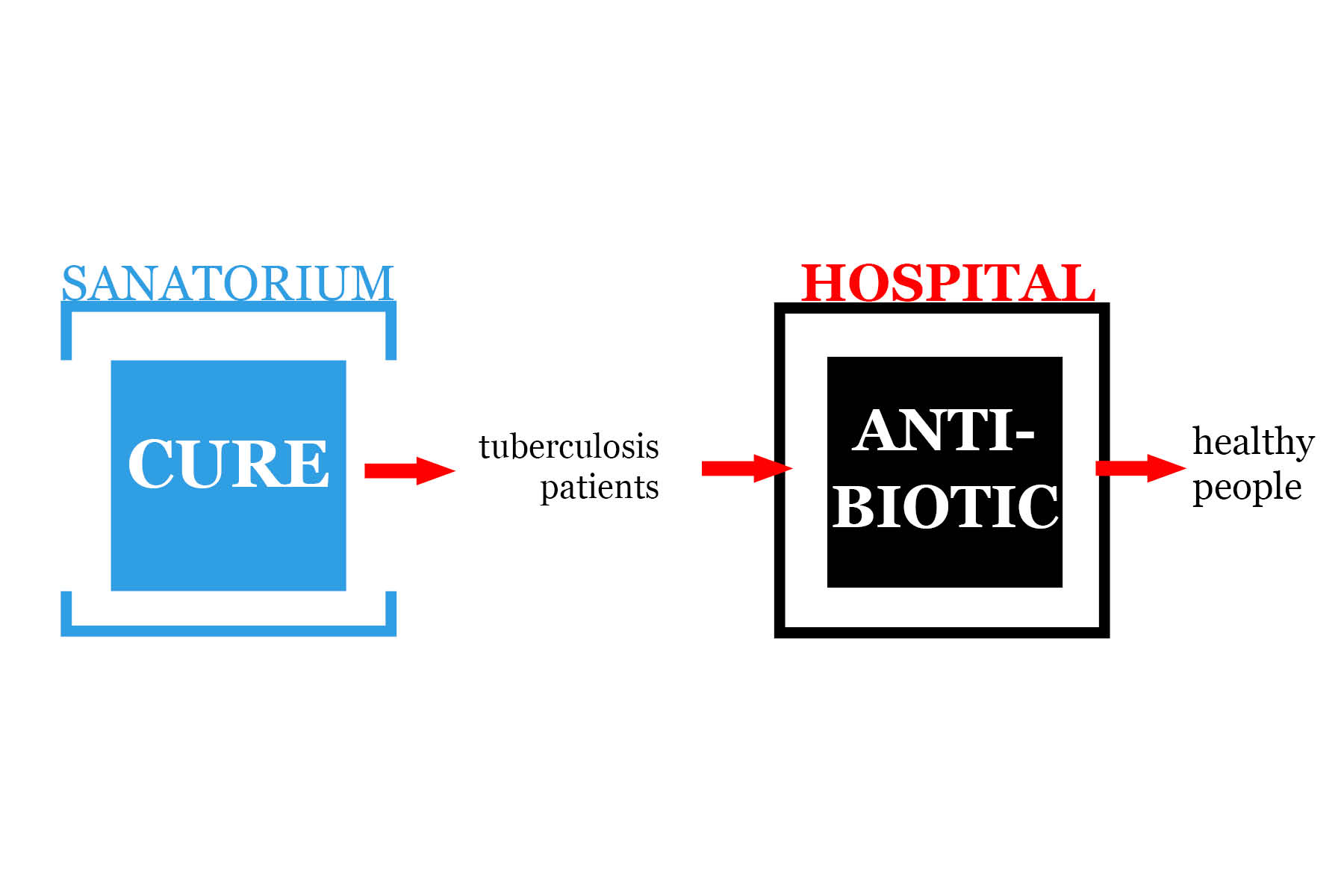

We assume that with the curative use of antibiotics, two phenomena occurred at the same time.

On the one hand, the buildings where tuberculosis patients were treated continued this curative function. The patients were treated with antibiotics and the institutions gradually extended their action to other pulmonary diseases to finally become general hospitals or be abandoned.

On the other hand, the natural curative device abandoned by the field of medicine, moved into the field of leisure, becoming a way of life limited to the period of paid leave.

This evolution, these two phenomena, made the sanatoriums disappear as an architectural proposal: their transformation into hospitals, using drugs to treat patients, made the treatment galleries and other architectural devices favoring the exchange between bodies and the environment disappear, while the attraction for the outdoor life that paid holidays developed favored instead light and transportable shelters: tents and caravans. The word “sanatorium” has become a word of the past.

The Paimio sanatorium, built by the Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, is a very good example of this phenomena. Comparing photos from the time of its construction (1933) with more recent photos, we can clearly see the closing of the treatment galleries by glass that Alvar Aalto himself supervised. Transforming an architecture that favors the exchange between bodies and the environment into an architecture that isolates them. In a way, the initial architecture has been denied.

One piece of furniture, armchair 41, more commonly known as the Paimio armchair, was specifically designed by Alvar Aalto for the sanatorium.

The general shape of the chair is perfectly suited to the function. Aalto explains that it is adapted to the objective of providing patients with an ideal position.

The angle between the seat and the backrest, he said, was to make it easier for the patient to breathe and to make the most of the sun’s rays during his treatment.

Like the sanatorium, the chair was designed with a cure in mind. The cure was abandoned. But the chair was not abandoned. Nor was it modified.

This chair is now part of the MoMA collection and is still produced by the company Artek. You can purchase it for 3238,80 euros. “Both monumental and airy, the Paimio 41 chair, created in 1931 as the result of a competition to design and equip the Paimio sanatorium, is one of the most beautiful chairs designed by Alvar Aalto.” One could say that, here, the use value disappears in favor of an exhibition value.

On the other hand, light and transportable, the outdoor deckchairs made of canvas and wood were able to leave the medicalized context of the sanatoriums to find themselves in the context of sunbathing on beaches and in the mountains.

The object is transportable and transposed from context to context. Contrary to the architecture of the sanatorium or the armchair 41, this chair was not invented for the cure.

It appeared in its current form to be installed on the deck of transatlantic liners when the weather permitted. This chair keeps the trace of this past by the name it bears: deckchair.

This object is special in its ability to adapt to new situations without losing the roots of its history.

It is a resilient object, but not amnesiac. It has taken care of us enough for us to take care of it.

One can even welcome its entrance at the Louvre Lens museum, near Roubaix; the first extension of the Louvre museum, which is also moving to a different context.

A row of deckchairs is arranged opposite the immense bay window that opens the museum hall onto the surrounding nature. We find here a paradoxical construction. Using outdoor furniture inside the museum, not as an object of the collection, but as an object of use. Placed in front of the window it tends to make the glass wall disappear, as if we were already outside. It is a question of showing that the museum is itself open to the environment, but only visually.

Here is perhaps where the sanatorial logic has come to ground in France: the museum as a simulacrum of the sanatorium. The museum dreams itself as a sanatorium, open to the environment, but it is only really a hospital, protecting its collections.

In the same way that the sanatorium is taken in a double contradictory movement of separation (separation of the patients from the society of the healthy ones, separation of the genders, separation of the patient and the carer) and of immersion (the bodies in the environment), the museum is the consecration of the separation of the works of art and the world, (the very notion of inalienable collection testifies to it), but also the possibility of the immersion of the public in the works.

« To recognize that the world is a space of immersion means […] that thre are no real or stable frontiers: the world is the space that never lets itself be reduced to a house, to what is one’s own, to one’s digs, to the immediate.”

Emmanuele Coccia. 2019. The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture. Cambridge: Polity, p. 43.

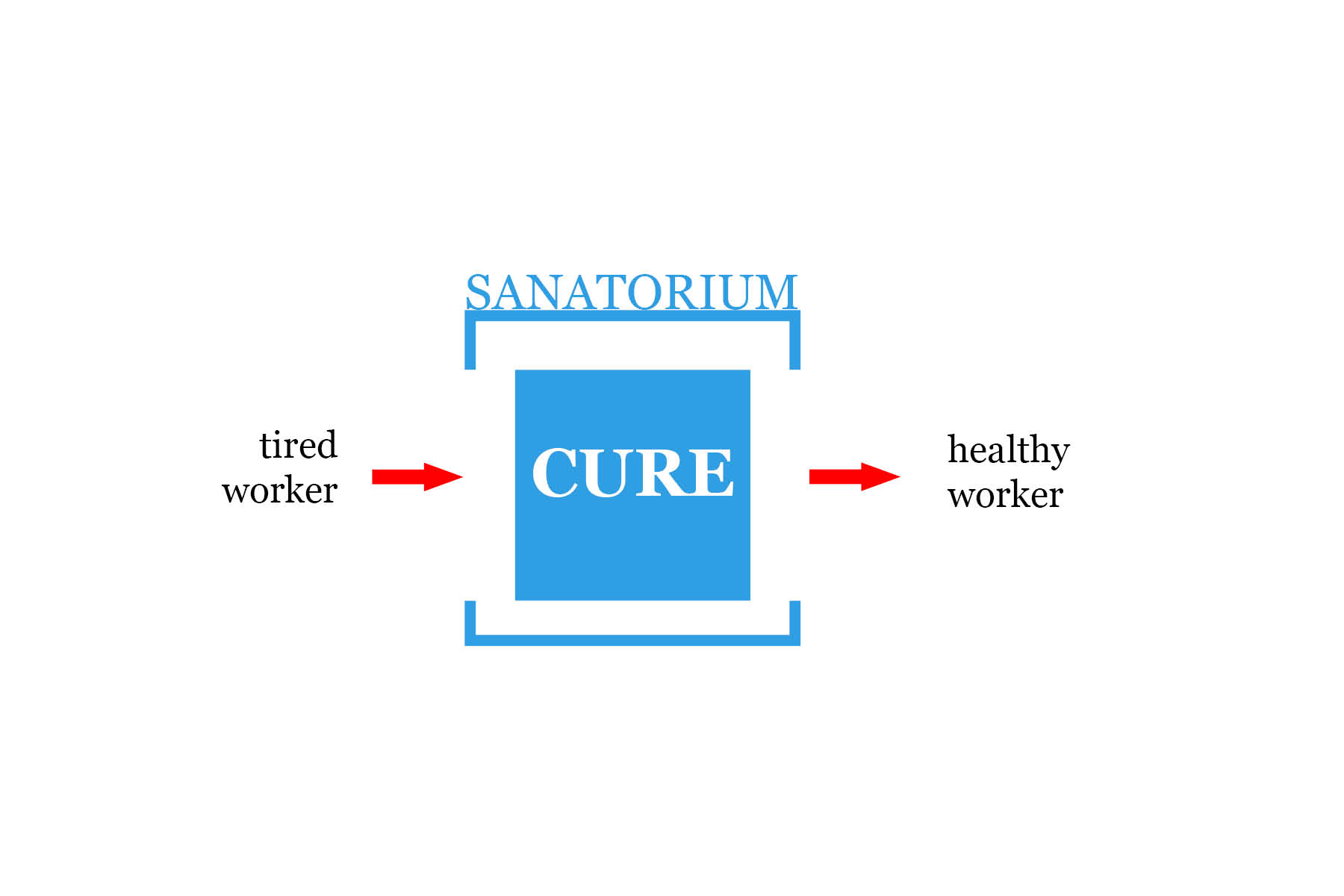

The word sanatorium, in all the countries of the former Eastern bloc, means today places that offer different body treatments, by means of essentially natural techniques: sauna, Turkish baths, salt sauna, sea baths, mud bath, massage… These establishments benefit from a positive reception.

The discovery of antibiotics and their effectiveness against tuberculosis after the Second World War in the Soviet Union and the occupied countries produced another movement than the one previously described.

There, tuberculosis patients left the sanatoriums to be treated in hospitals.

As they left the sanatoriums, the natural curative practice that was practiced there continued for another public: people suffering from non-morbid chronic diseases, or people looking for a certain well-being, or even, in some cases, the ruling officials that the regime thanked by offering them vacations close to those taken by Westerners, without it being said.

In other words, the building did not remain attached to the patients, but to the practice of the cure. In one case the sanatorium remained true to its architectural logic (open to the outside), but changed its social function, in the other case it remained true to its social function (curing the sick) but lost its architectural logic. So sanatorium and sanatorium does not mean the same thing depending on where it is pronounced.

Modernist functionalist buildings are often listed, protected and carefully restored. The Paimio sanatorium is an example of this.

Their architectural qualities are then mentioned, but these buildings have the particularity that they were built with the help of doctors. Initiated by the State, the architecture of sanatoriums was adapted to the cure. In France and Belgium, it was the Academy of Medicine that set the rules and approved or rejected the plans. Architects were no longer solely dependent on their order but also on the medical order.

The architecture created is based on standards that concern health. Then, these health norms fade away in favor of medicine. So we look at the building differently. And we start to find it beautiful. The function of architecture can be considered as an architectural quality or not. A question of context, no doubt.

Between East and West, the same word, having the same origin, covers today two opposite realities. This difference appears with the discovery of antibiotics.

Let’s remember where these antibiotics that have the property of killing bacteria or preventing them from growing came from. These antibiotics that led to the downgrading of sanatoriums as curative architecture come from a fungus: penicillium notatum.

This fungus, when it appears on the bread we are about to eat, we consider it a mold, making the bread unfit for consumption.

Moreover, mold in general causes health problems. In homes, the mold that we breathe causes various lung diseases of which asthma is probably the most common. One can die from an asthma attack. It is not harmless. The mushrooms which made it possible to save patients from tuberculosis also compromised the life of certain asthmatics.

But it is to them that we owe our atmosphere. If the evolution of land plants has greatly contributed to the transformation of our atmosphere, which allowed the emergence of animal life 450 million years ago, they were helped by fungi.

At that time, plants did not yet have roots, so it was the fungi that supplied them with phosphorus, a mineral essential for photosynthesis, which they drew from the soil.

We owe them the air that carries their spores and that we breathe.

The air, even purified, is a problem for the conservation of food. Often, we isolate the food product from the atmosphere. It is wrapped in an airtight film. On some packages it is stated that the product is in a protective atmosphere. But this nice name is specific to the French language and seems to be a marketing invention. In English, we speak of MAP (Modified atmosphere packaging), that is to say: conditioning under modified atmosphere, which is more correct since the atmosphere known as protective is an atmosphere in which one removed oxygen by replacing it by another gas in order to limit the development of the bacteria. In other words, French speakers would not survive in a protective atmosphere.

Here is what Bruno is working on in his workshop: a mushroom farm.

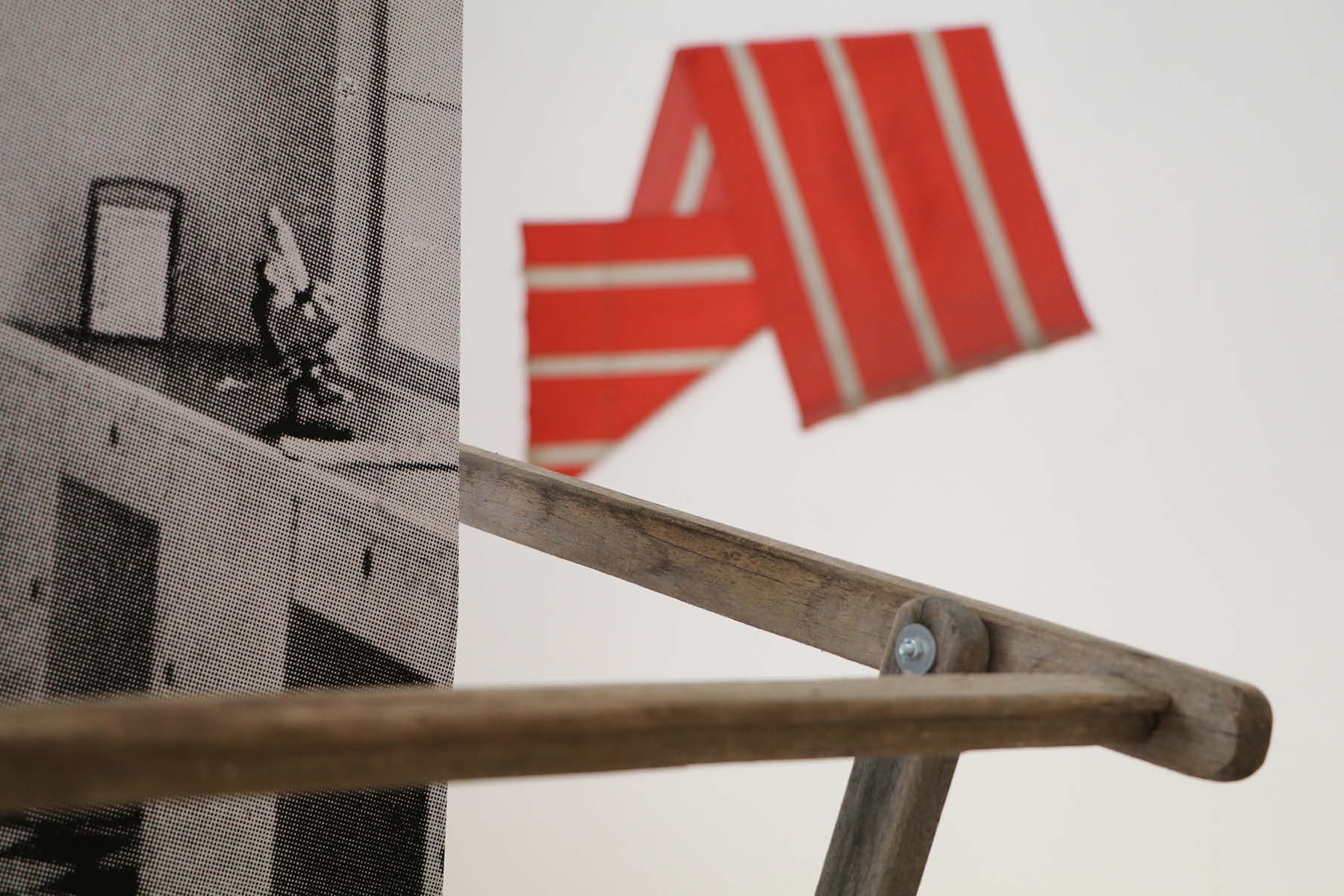

Little by little, an exhibition is being created in the Estonian context : there were deckchair structures, they were wrapped in cellophane (thanks to Covid?)

There were deckchair canvases hung on the wall as painted canvases could be. The separation of the structure of the deckchairs and the canvas of seat allowing to play again the games of separation of combination or exchange of which we mentioned.

In October 2020 there was still Covid-19. Estonia was not very affected at that time. So the country was protecting itself. It had not closed its borders, but it forced visitors to undergo a test, a quarantine, and then a second test 7 days later before they could travel freely. In addition, transportation, especially by air, had become erratic.

However, despite the discomfort and inconvenience of both the trip and the quarantine, Bruno found it necessary to come. While precise plans had been drawn, while I could without difficulty hang the exhibition myself, Bruno needed to come to Tartu. He wanted to build the exhibition, to be there, to be physically there, to experience it physically by doing it.

So, if we think about it, we can say that there is something at stake in this moment of the exhibition and its physical experimentation, something that passes through the body and that, in this sense, is the closest to what we are talking about.

We must insist on the physics of the body. This is perhaps a lesson to be learned from the health situation: at what point do we judge that the body is at stake, at what point do we judge that it must be preserved.

Yet the artist had prepared for a possible travel ban. He had plans for the gallery, had visited it with me in the summer, had made fairly accurate models of the exhibition and even label systems that would allow me to assemble the structures myself. He had therefore foreseen the possibility of not being on site. His absence would not have cancelled the exhibition. Yet, he wanted to be there. So what was his interest?

A virtual meeting had been organized, once the exhibition was installed, between Bruno, the co-curator, Liina Raus, and myself, all present in the gallery, and an art critic, who was at a distance. The critic had previously seen the models of the exhibition created by Bruno. When she saw the exhibition through a camera/screen, she thought that it corresponded well to the project, to what she had imagined (at least this is what we understood). It was strange for Bruno.

On the one hand, this remark suddenly negated the need for her physical presence – if the exhibition corresponded to her program, its practical implementation could have been delegated – on the other hand, it also tended to diminish the importance of the multiple choices that are only made in the moment and that seemed so important to us.

I saw that Bruno was trying to show the gap between the project and the realization, then very quickly, he gave up. Was it anecdotal, not interesting? What did it matter that the video was projected as soon as you entered the gallery, on the right wall, whereas in the project it had been envisaged to project it in the middle of the wall?

What did it matter that it was aligned with the bottom of the image to its left, that the upper edge of the image stopped at the light switches, that a poorly camouflaged electrical outlet was integrated into the projected image, that the projection took place at the point where the inclined plane joined the main floor, giving it a horizontality that it did not have, and above all obliging the spectator to interrupt the continuity of the image by projecting the shadow of his or her own body.

We can’t really say what it changes. But we realized that it changes everything.

In the retake that constitutes the moment of the exhibition, there is indeed something that is constituted differently, that surprises, something that makes it possible to say that it works, that it holds.

Something that makes an event of sorts, in the sense that what was initially produced is captured by the real presence of a body and a space arranged to move and affect it.

This is what the initial question of the response event that I addressed to Bruno produced: for him, as for me, it changes everything and leaves us speechless.

The Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa maintains that the experience of architecture is first that of a whole, of its atmosphere, that its reception is that of its atmosphere. He thus joins the philosopher Gernot Böhme for whom “the first object of the perception is an atmosphere”1; this sensation of a presence, being situated “upstream of any dissociation between subject and object” 2.

In the 19th century, the tuberculosis epidemic that raged in industrialized countries highlighted the primordial role of the environment on health. To the pathogenic environments of industrial development were opposed, as a cure, the healthy environments of sanatoriums. The cure proposed by the sanatorium system consisted in placing patients in healthy atmospheres. The atmosphere then communicates its properties to the subject who is bathed in it and experiences them.

Considering the atmosphere as the first object of perception makes it possible to reinterrogate the sanatorium as an environmental device, a machine for reconnecting bodies with the environment, upstream of the distinction that the effect of antibiotics on Koch’s bacillus has brought to light. And this also seems to us to have many links with certain practices that have developed in water cities: in Spa, Belgium, two tree-lined promenades have been laid out: the Four o’clock and the Seven o’clock promenades, where the bobelins (curists) used to meet by strolling around at the designated times. The schedule indicated in the rules of the sanatoriums is less restrictive here, but it operated in a very similar way for those who wanted to socialize and it is interesting to note that 90 schedule was inscribed in the public space.

The exhibition in Tartu seems to work in a similar way.

1Pallasmaa Juhani, Percevoir et ressentir les atmosphères, L’expérience des espaces et des lieux, Phantasia [En ligne], Volume 5 – 2017 : Architecture, espace, aisthesis, URL : https://popups.uliege.be:443/0774-7136/index.php?id=788.

2Böhme Gernot, Aisthetique, pour une esthétique de l’expérience sensible, les presses du réel, 2020, p. 55.